The MoviePass Saga: Rising From the Ashes, But Not Really?

By Dan McCarthy, Associate Professor of Marketing at the Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland

Originally posted on Linkedin.

Every year, I bring up MoviePass as an interesting cautionary tale of the role of unit economics and taking into account ALL of the various drivers of customer-based corporate valuation (CBCV), not just one or even all but one. MoviePass did not have an issue with with acquisition, retention, spend per customer, or CAC. But it had SUCH a big issue with contribution margin, that the whole business went down.

Every year, I update the story to account for what has transpired since I last talked about them. What was interesting this year is that in fact, a pretty fair amount has according to them.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, for the benefit of you readers who might not be quite as familiar with MoviePass, let me take a step back and summarize their history. In the world of subscription businesses, MoviePass is one of the most compelling, exaggerated-yet-surprisingly-common tales of the past decade.

Early History (2011-2017)

MoviePass was founded in 2011 by Stacy Spikes and Hamet Watt with a straightforward value proposition: pay $30 and $50 per month for unlimited movie access. The company grew modestly, attracting around 20,000 subscribers. While not explosive growth by venture capital standards, the unit economics made sense – the pricing covered the cost of tickets plus a small margin. It wasn’t an amazing business, but it chugged along.

The “Unsustainable Growth” Phase (2017-2019)

Everything changed in 2017 when Helios and Matheson Analytics acquired a majority stake in MoviePass and decided to put on the afterburners, slashing the monthly subscription price to $9.95 per month to watch up to one movie per day. Any movie. So you could watch a movie per day, 30 movies in total, and pay $9.95 for it.

A hell of a deal for the consumer!

But they were almost literally lighting money on fire.

The results were predictable – from a pure customer acquisition standpoint, it was a massive success. Subscribers surged from thousands to millions in months, reaching over three million by June 2018. Customer retention was strong, as consumers delighted in what was essentially a subsidized movie-watching experience.

But the unit economics were broken. MoviePass was paying full price for each ticket while often collecting less than the cost of a single ticket in monthly revenue. The more customers used the service, the more money the company lost – creating one of the few times where growing customer acquisition actually destroyed value and brought them to bankruptcy faster.

Long story short, by September 2019, MoviePass had shuttered operations, and by January 2020, its parent company filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation. The class action lawsuits were coming at them left right and center. It was a bloodbath.

The “Rising From the Ashes” Phase (2021-Present)

In November 2021, Stacy Spikes, who originally founded the company, regained ownership of MoviePass through a bankruptcy auction for just $140,000 – a tiny fraction of the company’s previous valuation.

Spikes relaunched the service in late 2022 with a fundamentally different approach. The new MoviePass featured a tiered credit system where subscribers pay as little as $10 monthly for a certain number of credits redeemable for tickets. The number of credits required varies based on factors like movie release date, showtime, and format. In higher-cost markets like NYC and Southern California, subscription prices were doubled.

By February 2024, MoviePass announced its first-ever profitable year in 2023, attributing this success to the new credit system and AI-powered inventory management. Recent press has celebrated this phoenix-like rise from the ashes, with headlines proclaiming MoviePass’s successful reinvention and newfound sustainability. And even an investment from Comcast. The old management was out (and pleading guilty to securities fraud). The new (new old?) management was in and the turnaround was in full force.

Where They Are Post-Reset

What I wondered was just how much the company had risen from the ashes. It was clear that the unit economics were back on track. The contribution margin was OK again. But what exactly did this do to the other CBCV drivers? In particular, I was wondering about customer acquisition. Did enough people find this new value proposition, which while more rational, was not nearly as attractive and kind of confusing? And how about retention — was this compelling enough that those who adopted stayed?

To answer these questions I reached out to my friends at Earnest Analytics. They have some of the best credit card data out there. They can see everyone who has transacted with MoviePass through the credit card statements, which allows them to know to what extent the business has come back to life, and how customers are monetizing these days.

From what I can gather, the story is mixed.

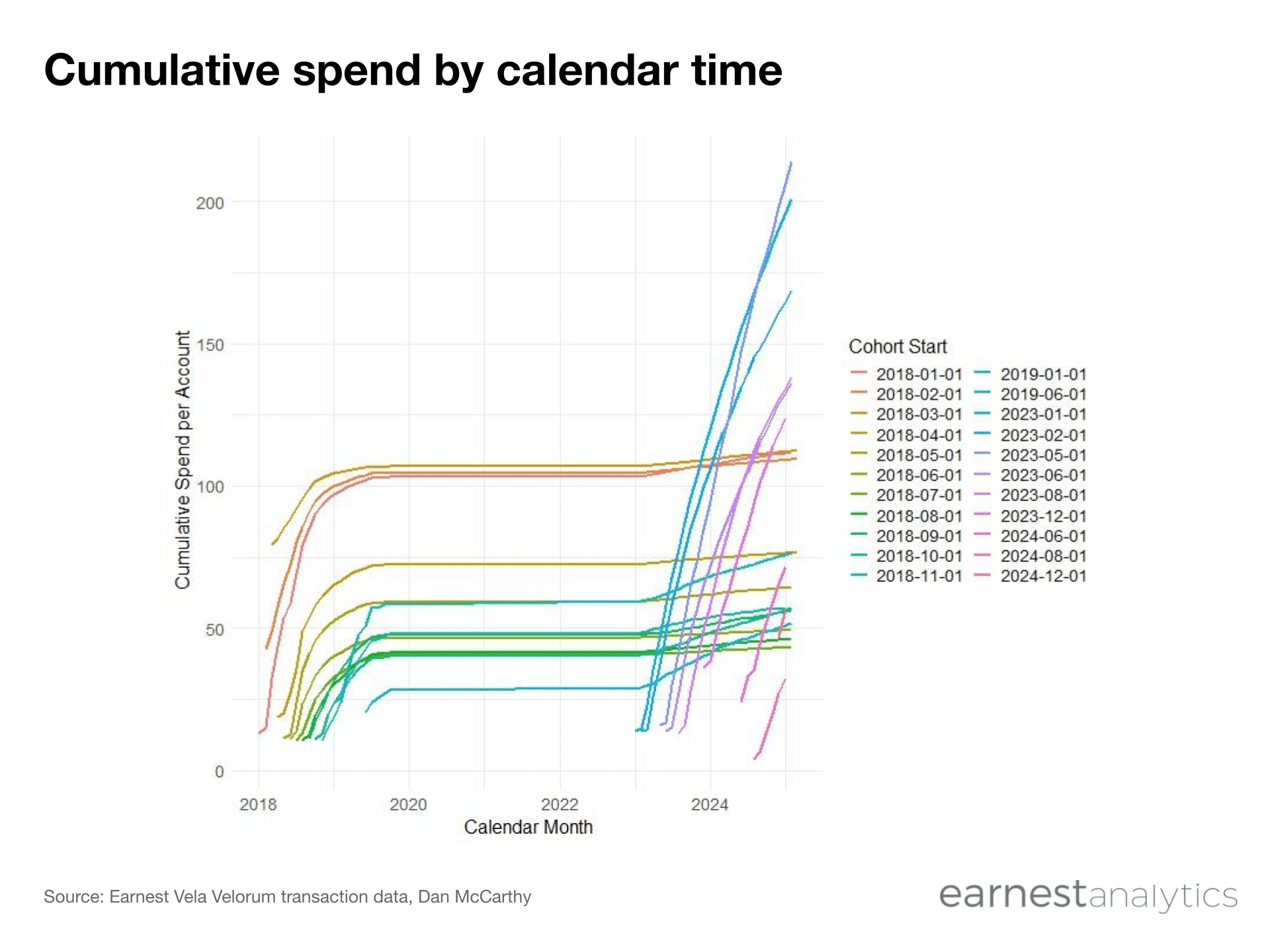

Good News: Customer monetization has significantly improved post-relaunch. Where previously the company struggled to extract more than $100 in lifetime revenue per customer after one year, current cohorts are generating well over $125 by the same point, with some reaching $200+ cumulatively.

Below is chart that shows cumulative spend per customer by acquisition cohort over time:

Of course, one of the big reasons why the earlier cohorts stopped monetizing was because MoviePass was going under. But it is nevertheless heartening to see the cohorts monetizing well over relatively longer periods of time. $200 per customer is not a small sum of money!

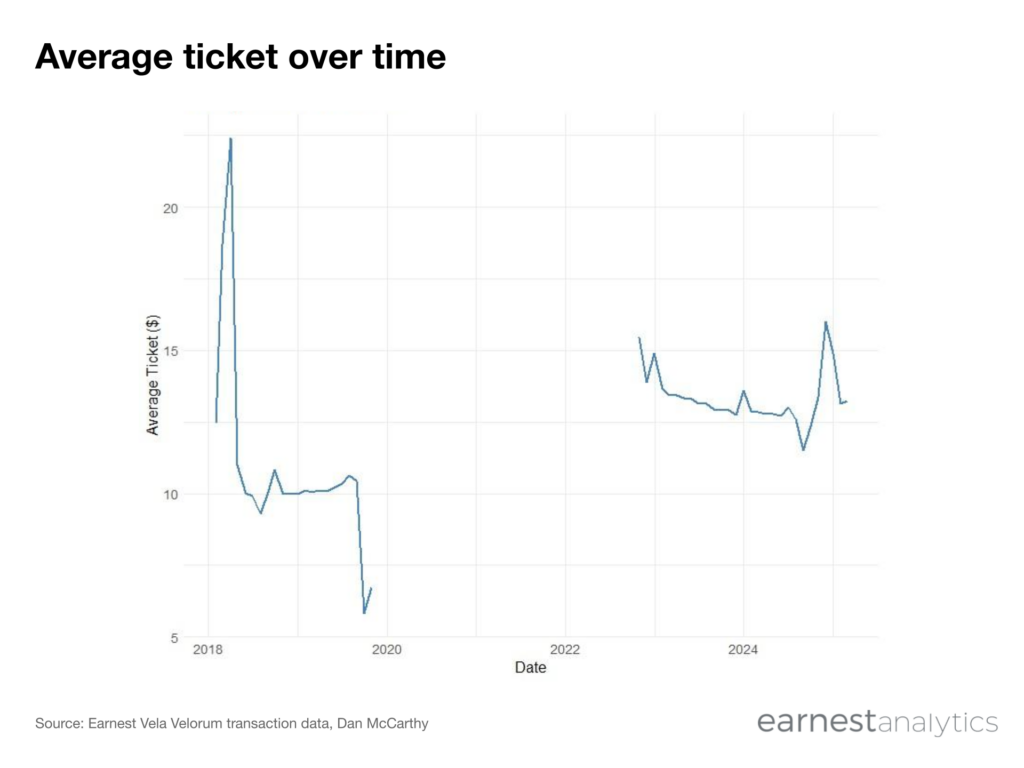

Average spend per purchase is higher to boot, post-reset:

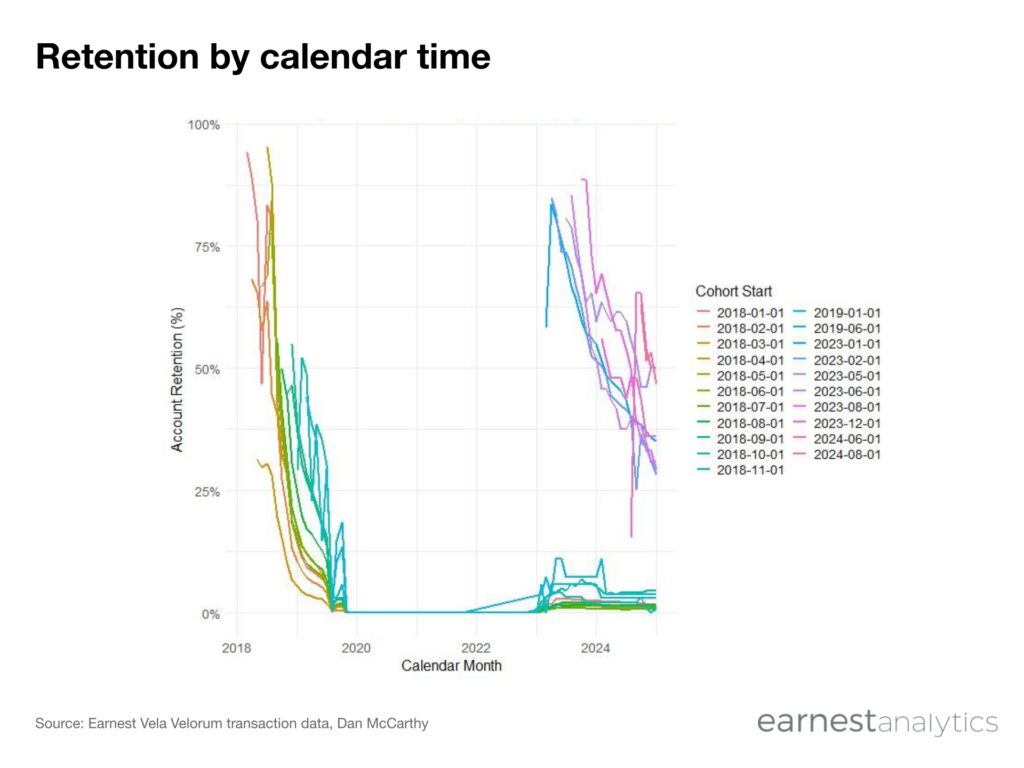

If you stare at the retention data in the right way, you would see that retention is not worse post-reset:

All good signs that when customers are acquired, the economics look pretty good.

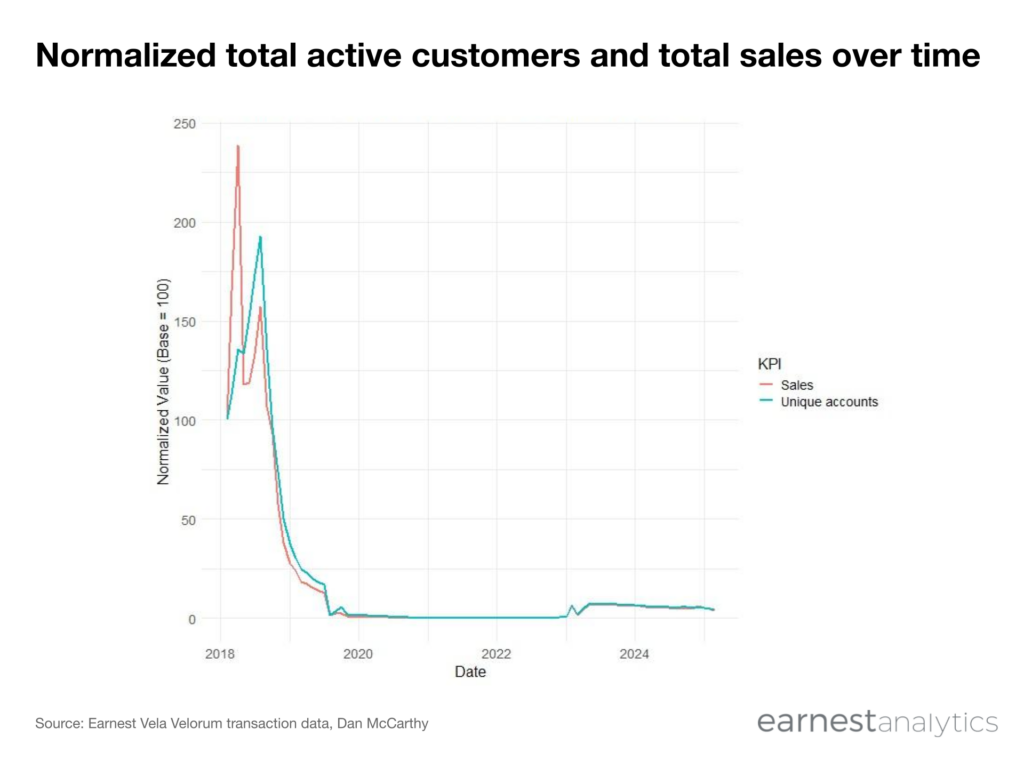

Bad News: The bad news is that calling the scale of the business “dramatically smaller” would be an understatement. If we index to January 2018 levels, current sales hover at approximately 4% of where they once were. Yes, you read that correctly – 4% of their early 2018 size. Many cohorts have so few customers that meaningful trend analysis is difficult.

Customer acquisition has fallen off a cliff.

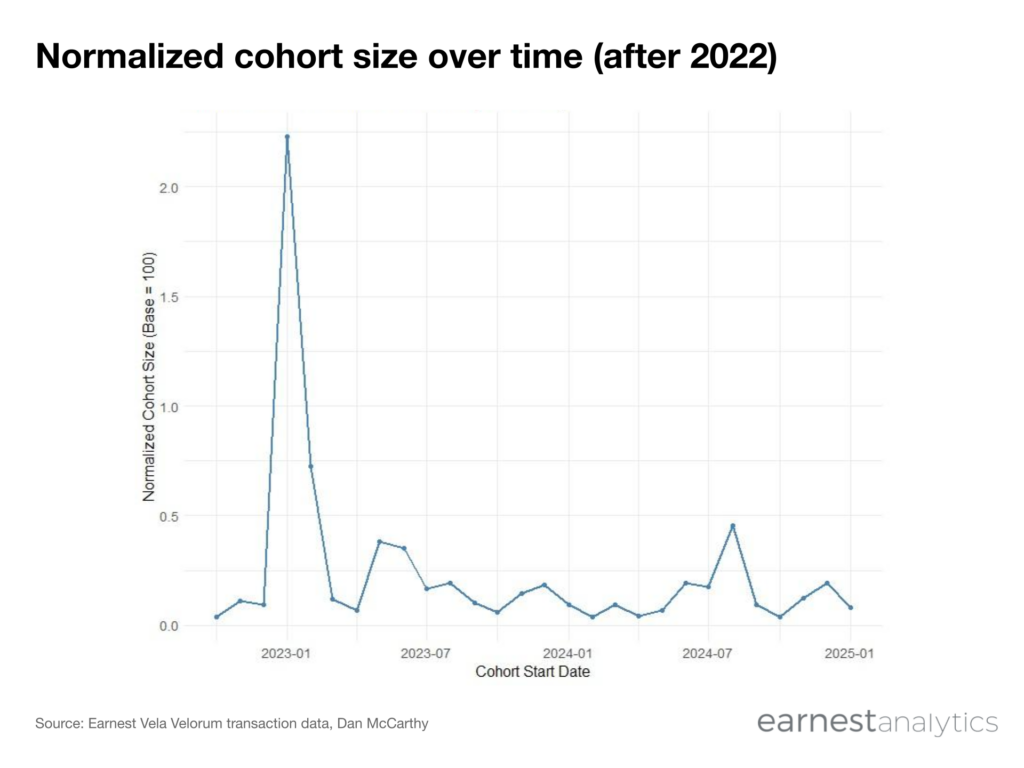

And they are not really growing — in fact, after a spike in activity in January 2023, they are arguably shrinking:

So the economics of the customers they acquire are dramatically better, but the volume of customers they can bring is a small fraction of what it used to be, and falling, not growing, in recent months.

Summing Up

The MoviePass saga perfectly illustrates a fundamental business reality: you cannot outrun poor unit economics and you cannot ignore any of the CBCV drivers. Get even one of them wrong enough, and it can be fatal for your business if it’s in bad enough shape.

Prioritizing growth at all costs and expected profitability to follow at some unspecified future date does not cut it. But on the flipside, if you prioritize solid unit economics, the risk can be that it’s just not that attractive to customers and customer acquisitions suffers. There are inherent tradeoffs between the drivers and what is best is not always obvious.

You may think, “Oh, MoviePass was extreme, that would never happen to other businesses!” But similar patterns emerge across industries. Consider Wayfair, struggling with high customer acquisition costs and slim margins. Or look at ChatGPT, which is currently facing some serious questions about contribution margins given all the cash they’re burning through. I’m not saying these companies are destined for MoviePass’s fate, but the general story of “super fast growth and negative margins that will hopefully improve at some point” is more common than you might think. The lesson remains the same: sustainable unit economics cannot be an afterthought.

Request information on subscription spending